Midwinter Solstice: Return of the light

Sine umbra nihil

MIDWinter Fire festivals were ancient man’s most fervent prayer to the Universe to return the light to the earth after the shortest day.At 57º North latitude in Scotland, the equivalent in North America of the parallel of Juneau, Alaska, there aren’t a lot of hours of light in December and January. By the time solstice – the day the sun appears to stand still – December 21st – arrives, ancient man was getting to the point where it was going to get dark forever, unless something was done to propitiate the spirit world.

In the earliest known Calendars devised by Arabian astronomers, even the balmy latitudes of the Mediterranean and Arabian Seas saw a dwindling of the light. And so when Neolithic man erected stone circles and sacred precincts of stone leading the eye to the horizon to a point where the sun set on midwinter’s day, he did it for a most urgent purpose: to ask the Light of the Universe, the Sacred Fire, to return.

What better way to kindle the blessing of the gods of light and fire than with fire itself?

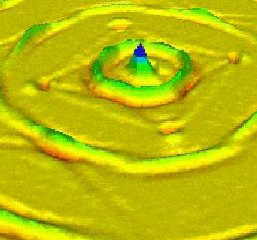

In Northeast Scotland, where recumbent stone circles abound, the recumbent or ‘resting’ stone lies in the southwestern quadrant of the circle, flanked by two carefully chosen pillars of stone (quartz, quartzite, granite with inclusions to reflect the light), creating a window on the horizon where the midwinter sun goes down. At 4:00 p.m.!

It is more than seventeen hours before it rises again. Seventeen hours must have created an enormous hiatus of doubt and disbelief in the minds of ancient communities whose shaman or holy man might be the only one who knew the light would return. But did they? It is no wonder that oral tradition handed down tales of the supernatural abilities of such knowledgeable men.We have no record of how such workers of celestial magic were named in the time of the first farmers, the Neolithic communities who raised the megaliths of Aberdeenshire.

But by the time of Roman historians, like Tacitus and Ptolemy, who wrote of ancient Britons’ ‘great powers’, Roman respect for the Celtic peoples of Europe and the Druids of the Britannia was great. Ptolemy and Caesar record phenomenal belief by the people in their magicians, their Druids, their ‘keepers of knowledge’ and rightly so. The Celtic traditions known to the Gauls owed their origins to the British druidic élite. Much veneration and respect was paid in Gaul to this small group of islands lying in Ultima Thule, or in Roman slang ‘off the map’ on the edge of the Roman Empire.

Certainly by the time of our Pictish ancestors – those whom the Romans called the Caledonians – stone circles were in constant use for fire festivals and seasonal rites of propitiation for the welfare of the community. The Picts also had their own druidic priest class like those of Wales and other Brittonic peoples. And their power to be seen to command the elements of fire, water, wind and earth were extraordinarily great. Annals and documents from Gaul, Cornwall, Brittany and Rome confirm their hold over the people, not only to guide farming work through the annual cycle, but also to act as advisor to queens and kings.By the ancient Celtic calendar, known to the Romans as their equivalent of the Julian method of calculation, there were ten months in the year and thirteen moons. Man moved according to the sun for daily light and warmth, but owed allegiance to the moon for rhythms of planting and harvest, the female menstrual cycle and hence the cycle of birth and death. The Julian calendar was a ruling force for fifteen hundred years, until it started to lose time.

By then the Church, mathematicians and enlightened astronomers had stepped in to alter the rhythm to run more closely with human time. Most nations changed over to the new calendar after it was decreed law by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. But the Orthodox Greek and Russian Churches refused to change. Other nations remained staunchly in favour of the older calculation. Among these were Ethiopia and Russia, who did not accept European calendar reckoning until 1750. Ethiopia still does not.

And Burghead in Moray.

In Burghead they burn the clavie to celebrate the return of the light of a dying sun. An ancient rite practised on the night of solstice in pre-Christian times, to propitiate and ask the dying sun to return, its confused calendrical transposition to January 11th can only be slightly rationalized by calendar change. Nevertheless, it is on this date that Burghead has through oral tradition and in living memory rekindled and paraded its torch of blazing fire.

It’s a little more complex than merely holding to the old calendar. Well-wishing for a new year is what we do in the Northeast of Scotland when the calendar points to January. It’s called Hogmanay. It was always so. Or was it?

In Gregorian, we count this as 2009; about to go 2010. It is already 5770 Jewish time. The month of February 2010 opens the Chinese year of the Tiger; on February 22 Islam moves into 1431. For Sikhs, new year (542) comes just before vernal equinox when Hindus (2067) and Persians (1389) celebrate, just as we used to before the Julian calendar adjusted new year from March to January.

This is no surprise to the Clavie Crew of Burghead on the Moray coast. They still run on Julian time.When Scotland changed calendars in 1660, there was much misunderstanding in country districts – the loss of 11 days was seen as someone in a position of power having robbed them of important events. This was also a period of change in parishes because of the implementation of new church doctrines introduced at the Reformation. Calendars in Church records added to the confusion by writing numbers in ‘Old Style’ and ‘New Style’. It caused so much concern that Old Parish Records (OPR) had to show both systems. Births in the OPR are recorded for several years in both Old and New Time.

Also at the Reformation pre-Christian festivals, such as clavie-burning and fire festivals at Beltane, Hallowe’en and harvest too, were frowned on. On the other hand, local tradition was strong: it was commonplace to mark the return of the light after midwinter in all northern communities and northeastern ports. Such pagan celebrations as ‘fire leaping’ and dancing round the fire within the precinct of stone circles was still known in 1710 and harvest fire festivals continued unabated until the year 1942. Gradually, however, other celebrations and farming fire festivals started to die out.

When the other northern ports stopped their Clavie burning in winter after the first World War, Burghead held on. After the second War, it continued to celebrate as it had always done. It has continued to do so ever since, except for two of the years during the 1939-45 European War.

Now only two villages hold to the ancient tradition: a pre-Christian ritual of celebrating the closing of one seasonal door and the opening of another.

Stonehaven in Kincardineshire celebrates with a street festival of fireball-swingers. Both festivities are awe-inspiring, if marginally dangerous to watch. It must be awesomely perilous for those involved. On Hogmanay night Steenhivers have a street party to end all street parties. Whereas Burghead only spills combustible materials over the shoulders of Clavie-bearers, Stonehaven delights in spinning fire in clumps into an unwary crowd.

Stonehaven has conceded to the newer calendar, swinging its crazy fire balls on Hogmanay; yet it is celebrating the same midwinter seasonal hinge as the Clavie Crew of Burghead: The end of the Old Year; Old Yule: Aul’ ‘Eel.

Burghead is more precisely still counting its eleven lost days.

In Burghead, lighting the eternal fire and carrying it round the town reenacts the celebration of the return of new light after the longest night in the Northern hemisphere – the dark of the Latin quotation often found on sundials: ‘without shadow there is nothing’. Implied, naturally, is the fact that the all-important entity which creates shade in the first place, is the Sun.

To the Clavie King and his torch-bearers of Burghead, this is Aul’ ’Eel, pre-Christian Yule or winter solstice. Yule becomes interchangeable with Christmas south of the border but Scotland has held to its pagan festival of Hogmanay, itself a testimony to and turning point in that Roman calendar.

Fire for the clavie is ritually kindled from a peat ember – no match is used. This is in respect for the spirit of fire itself which is eternal.

The Clavie itself is an old whisky barrel full of broken up staves ritually nailed together by a clavie (Latin, clavus, nail). One of the casks is split into two parts of different sizes, and an important item of the ceremony is to join these parts together with the huge nail made for the purpose. The Chambers’ Book of Days (1869) minutely describes the ceremony, suggesting that it is a relic of Druid worship, but it seems also to be connected with a 2000-year-old Roman ceremony observed on the 13th September, called the clavus annalis. Two divisions of the cask in the Burghead ritual symbolize the hinges of the old and the new year, which are joined together by a nail. The two parts are unequal, because the part of the new year joined on to the old is very small by comparison with the old year which is departing.

Clavie King Dan Ralph has carried out his duty for twenty years. He gathers together his Clavie Crew and they help each other take turns carrying the man-sized torch: a tar-barrel stoked with oak staves soaked in combustible fluid. It is a feat of human endurance alone to lift what must weigh more than a man, not to mention avoiding flaming drops of leaking fuel. They stagger in unison round the town, dispensing luck as they go: flaming brands from the burning tar-barrel are presented as tokens of abundance to important burghers, including the publican. The bearers keep changing; circling the town sunwise, stopping only to refuel or change carriers. A final free-for-all happens after the clavie arrives at the fire-altar hill, on a rib of the old Pictish ramparted stronghold, which juts out into the Moray Firth. There it is fixed to its fire-altar, the doorie.More tar, petrol, any source of incendiary fuel is added until the flames reach for the heavens. Then both fire and wooden vessel, the fast-distintegrating clavie, and its lethal blazing contents are left to die.

Happy New Year. Julian indeed.

December 6, 2009 - Posted by siderealview | ancient rites, astronomy, crystalline, culture, nature, Prehistory, ritual, sacred sites, stone circles, sun | Aberdeenshire, Aul' Eel, Auld Yule, barrel, Burghead, burning the Clavie, calendar, cask, Clavie King, Dan Ralph, Druidic knowledge, festival, fire, fire-festival Gregorian, hinge, Julian, midwinter, Moray, Northeast Scotland, oak staves, old calendar customs, Pictish, ports, quartz, Russia, solstice, stonehaven, swinging fireballs

4 Comments »

Leave a comment Cancel reply

About

Lots of writers use a nom de plume to distinguish between their personae – it’s the way publishing works. Blogs, too. What choice, what abundance: we can be guided by all our Muses and still retain our integrity (who doubts it?)if we are prone to take one persona more seriously than another. For this blog I become this particular blogger because the material is time-sensitive; the research is all coming together now and our way forward is mapped. That said, it’s up to us whether we take the information and run with it.

Top Posts

- March In Like a Lamb,Out Like a Lion:Does Ancient Rhyme Predict More Climate Crises or Solutions?

- February Packed Full of Festivals Both Ancient & Modern—an Unholy Cultural Mix North and South of Equator

- Stepping Ahead into 1st Quarter of 21stCentury While Looking Back to the Goode Olde Days

- Sun's Coronal Hole-Combo-Climate Crisis Make for "Interrresting" December Human Conditions +Airliner Surprise

- November Remembered for 'Gunpowder, Treason & Plot':420yrs Later Have We Learned Anything?

- Warmest Year on Record: 2023 "October—All Over"? No Chance as Angels Are With Us

- September-Remember: As Autumn Hits, Human Tragedies are Hard to Forget but Human Kindness Wins

- Lammastide/Lughnasadh LightFest, Lionsgate, Two Full Moons in August +Tropical Cyclones & Hurricanes

- Fireworks in U.S.,Tropical Cyclones, as Brits swim into their Summer Hols thru Torrential Rain

- Atlantic Hurricane Season Echoes Pacific Cyclone in GUAM/MARIANA Is. Heralding Earth's Hottest Summer Yet

YoungbloodBlog Stats

- 117,019 hits

-

Latest posts

- March In Like a Lamb,Out Like a Lion:Does Ancient Rhyme Predict More Climate Crises or Solutions?

- February Packed Full of Festivals Both Ancient & Modern—an Unholy Cultural Mix North and South of Equator

- Stepping Ahead into 1st Quarter of 21stCentury While Looking Back to the Goode Olde Days

- Sun’s Coronal Hole-Combo-Climate Crisis Make for “Interrresting” December Human Conditions +Airliner Surprise

- November Remembered for ‘Gunpowder, Treason & Plot’:420yrs Later Have We Learned Anything?

RSS Feed

astro

Youngblood BlogArchives

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- September 2014

- June 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

The Stellar Perspective

The Stellar Perspective- Oriental Year of Dragon 2024 & Lunar New Year Zodiac

- Early Saints & Religious Houses in Scotland with Placenames derived from Pictish/Brittonic/Celtic

- U.S. Memorial Day Means Different Strokes for Different Folks

- Hokole’a Hawai’ian-built Canoe to Circumnavigate Pacific— 47,000 Miles over Next Four Years

- Time to Tempt Humans to Act like Telosians—Delving Deep Within to Discover our Origins As Star-People

- Canticle for a lost Nation—Pictish Roots Surface in Stone, Royal Forests & Names

- The Janus Effect—Riding into the New on an Old Horse

- Boudicca: Great Queen of the Iceni

- 2020 Backward Take on 2012: Stargate Portal to Final Quarter

- Volcanic Surprise: Take your Toys and Go Home

Youngbloodblog calendar of posts

Solar & Geomagnetic field indicator (NOAA)

From n3kl.orgSolar X-rays:

Geomagnetic Field:

Meta

Derilea’s Dream: Pictish essentials

Derilea’s Dream: Pictish essentials- The Glory that Was Sail

- Guest Blog from the Granite Past to a Future Historian

- Boudicca: Great Queen of the Iceni

- The Sueno’s Stone Cover-up

- Maiden Stone of Bennachie

- Bibliography: The Church in Pictland

- Warlord centres of Pictland:glimpses into a lost history

- Gaels progress through Pictland via the Church

- Hello world!

Shakeout prepared

Related Pages

Picosecond Pulse Ripples Gold on Glass

Recent Comments

Marian’s SHASTA:Critical Mass

bumpy ride ahead

‘Phantom’s Child’

Nano 2011 win

Weblog Pages

SHASTA: backstory

-

Join 605 other subscribers

Circlemakers

Enchantment

Blackbird pie tweets

Tweets by siderealviewShakeOut preparedness

Bourtie Kirk: 800 Years

Geometry code

Cloud of Thought

Aberdeenshire agents Alex Cavanaugh Alex J Cavanaugh Amazon astrology Aurora Borealis autumn Baby Boomers Bahamas blogging bloghop Buchan Burning Man Caledonian Forest Caledonian Pine calendar candlemas consciousness crop circles deadline Deeside earthquake Easter eclipse equinox fiction fire festival fireworks Forteviot full moon Glorious Twelfth Grand Cross Green Turtle Cay Groundhog Day Hawaii Hogmanay humpback whale Iceland iGen Insecure Writers Insecure Writers Support Group IWSG Jupiter Klamath River lammas light Mardi Gras Mars Mercury moon Moray Moray Firth Muse NaNoWriMo Neptune new moon novel ocean Pisces rewilding Rome Saturn sci-fi Scotland Scots Pine snow solstice Uranus Venus volcano weather WIP writing Yurok Devorguilablog: view from Pictish Citadel

Devorguilablog: view from Pictish Citadel- Pictish Power Centre discovered at Rhynie: stronghold in Aberdeenshire heartland

- Black Glen Cailleach/Bodach Stones threatened

- PICTISH KINGLISTS and the PICTISH CHRONICLE

- Nechtan’s Pictish Nation: 8thC Strongholds of the new religion

- Pictish inheritance in an ancient land

- Canticle for a lost Nation

- Canticle III: Nechtan of Derley

- Devorguila’s lineage: where did it go?

cosmic consciousness

Archives

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (1)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- September 2022 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- July 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- March 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (2)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (1)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (2)

- January 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)

- September 2018 (1)

- August 2018 (1)

- July 2018 (1)

- June 2018 (1)

- May 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (2)

- November 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- October 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (1)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (1)

- April 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- February 2016 (1)

- January 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (1)

- October 2015 (1)

- August 2015 (1)

- July 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (1)

- April 2015 (2)

- March 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- March 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- November 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (1)

- July 2013 (1)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (1)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (1)

- February 2013 (1)

- January 2013 (1)

- December 2012 (1)

- November 2012 (1)

- October 2012 (1)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (2)

- July 2012 (1)

- June 2012 (2)

- May 2012 (1)

- April 2012 (2)

- March 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (1)

- December 2011 (2)

- November 2011 (1)

- October 2011 (1)

- September 2011 (1)

- August 2011 (1)

- July 2011 (1)

- June 2011 (2)

- May 2011 (1)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (2)

- February 2011 (1)

- January 2011 (1)

- December 2010 (1)

- November 2010 (2)

- October 2010 (2)

- September 2010 (3)

- August 2010 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- June 2010 (1)

- May 2010 (3)

- April 2010 (3)

- March 2010 (3)

- February 2010 (2)

- January 2010 (1)

- December 2009 (5)

- November 2009 (5)

- October 2009 (2)

- September 2009 (3)

- August 2009 (3)

Youngblood issues

- ancient rites (71)

- art (55)

- Ascension (23)

- astrology (54)

- astronomy (48)

- authors (141)

- autumn (2)

- belief (50)

- birds (25)

- blogging (122)

- calendar customs (71)

- consciousness (47)

- crop circles (18)

- crystalline (11)

- culture (143)

- Doomsday (3)

- earth changes (42)

- elemental (8)

- energy (33)

- environment (76)

- fantasy (33)

- festivals (64)

- fiction (87)

- gardening (24)

- history (76)

- Muse (55)

- music (11)

- nature (72)

- New Age (17)

- New Earth (35)

- novel (58)

- numerology (4)

- ocean (28)

- organic husbandry (22)

- poetry (2)

- popular (38)

- pre-Christian (34)

- Prehistory (22)

- publishing (88)

- rain (21)

- ritual (44)

- sacred geometry (7)

- sacred sites (39)

- seasonal (71)

- seismic (18)

- snow (1)

- space (5)

- spiritual (20)

- stone circles (13)

- summer (5)

- sun (30)

- traditions (60)

- trees (25)

- Uncategorized (9)

- volcanic (19)

- weather (52)

- winter (25)

- writing (138)

[…] This post was Twitted by FraserGeddes […]

Pingback by Twitted by FraserGeddes | December 6, 2009 |

[…] in keeping Pictish tradition, celebrating the sun’s return after winter solstice by “Burning the Clavie” – a man-size torch carried sun-wise round the town on the shoulders of the clavie king […]

Pingback by Maiden Stone of Bennachie « Derilea's Dream: Memoirs of a Pictish Queen | December 15, 2009 |

[…] calendar, both originally, like all early societies, based on a lunar month. The sixteenth century Gregorian calendar altered our thinking to calculating almost exclusively in solar time. The oriental calendar, […]

Pingback by Candlemas: orward or back « Youngblood Blog | February 2, 2010 |

[…] from the previous Julian calendar when in 1752 country people in Britain rebelled at being deprived of 11 days of their precious time. ‘When Gormire riggs shall be covered with hay, The white mare of […]